Arahmaiani photographed in front of Dutch Wife, 2013 at Tyler Rollins, Janaury 2014

© 2014 by Chrysanne Stathacos

SUSAN:

I wanted to start by asking you how you developed your practice as a performance artist and who your role models were, if any, because it seems to me that choosing performance might have been unusual in the context that you were in at the time, especially for a woman.

ARAHMAIANI:

When I started I didn’t even know it was called performance art. Only later when some curators coming from Australia and Japan, I think it was in the early nineties, said, “Oh, you are doing performance art.” “That’s how you call it? Performance art?” And they said, “Yes, you don’t know that?” Anyway, if you ask me for a role model, actually at the beginning I didn’t really have a role model. It was just a kind of urge that I had at the time. I was taking this painting studio class, I was at art school then, and I felt somehow limited by the canvas and paints and also the problem was that the materials were very expensive and I was just a young artist, but really energetic. As a kid I was trained as a dancer and also as a martial arts master—because my grandfather was a martial arts master—and then the performance world was something I was familiar with, so then I began to try to express myself through this kind of medium and also because it’s somehow very cheap and I know there is more freedom, I can express in this kind of medium. So that’s the beginning of my performance work.

SUSAN:

In conjunction with that first question, I don’t know how strict Indonesia is about following Muslim rules of propriety, but I wonder if it was an issue that a woman was performing in front of people? Did it ever become a religious issue? I would think that it is a feminist act in that context for a woman to put herself in the public sphere, especially since stricter versions of Islam want to keep women restricted to the private sphere. Isn’t it a radical act in itself to place yourself in the public sphere as a performance figure?

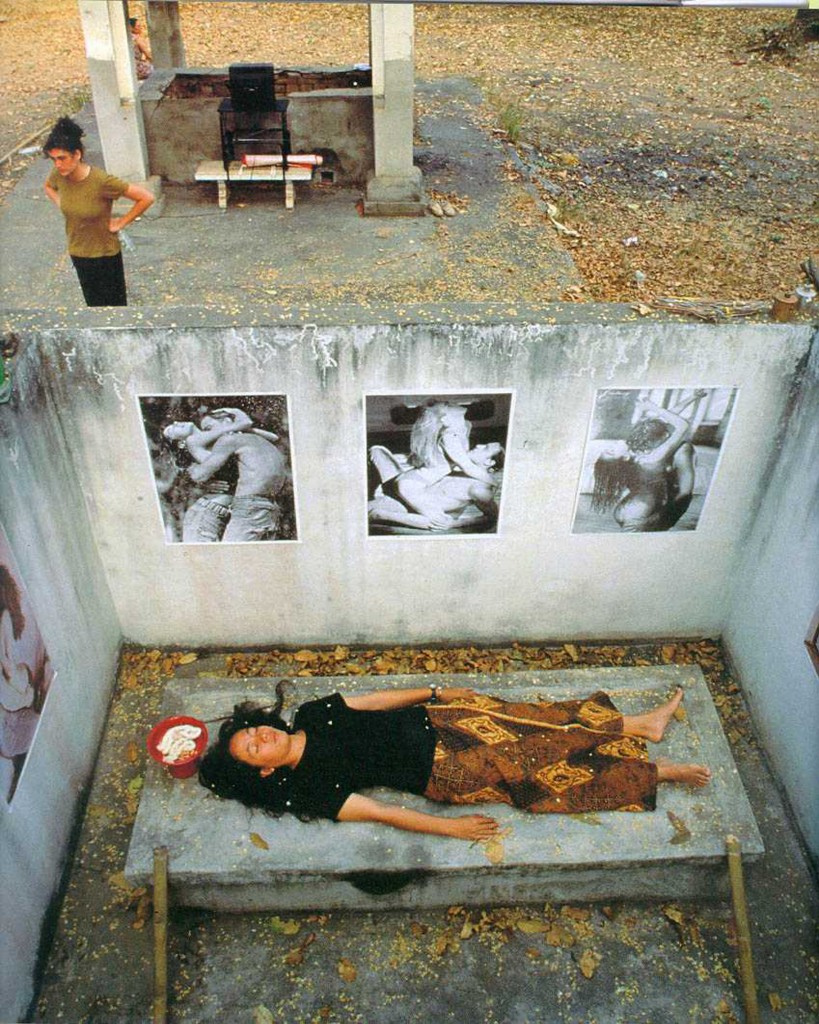

Accident, 1980 (Performance, Bandung, Indonesia) photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

ARAHMAIANI:

Muslims in Indonesia are the largest group, almost 90% out of almost 235 million people now. But there are different groups. It is not like one general following, there are a variety of groups with different practices of Islamic culture, but there are some who considered not only a woman but performance itself to be non-Islamic, or not encouraged. It is more like a conservative, almost hard-liner group. So for example, my grandmother from my father’s side, when I studied, she was really worried that I was going to have a performance in front of the public. And I said, “Yes, why not?” Wow, that doesn’t sound good, you know, for her. But somehow there was my father in between and my father is quite moderate and he’s a religious leader but he was educated here at Columbia University and at Oxford, so somehow he is modern. He is a religiously responsible leader and I often get his permission to do something that is not so traditional or something more modern.

Offerings from A-Z, 1996 (Performance, Padaeng Crematorium, Chiang Mai, Thailand) photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

CHRYSANNE:

Because of your activities you were imprisoned. It was in connection to your piece in which a condom was displayed next to the Koran. I understand that this piece resulted in a lot of hostility. Can you tell us a bit about this? Did you have to leave Indonesia?

SUSAN:

And weren’t you also imprisoned when you were a student?

ARAHMAIANI:

Well, these were two separate things. I was imprisoned because of my performance on the street. I was still in art school and this was a problem with the military regime. We were under the dictatorship of Mr. Suharto at the time, so the military regime then was really oppressive. I was arrested for about one month, until they released me with the conditions that I cannot do any public activities or exhibitions. And this was terrible of course, I was young then and I had a lot of energy and I wanted to do a lot of things, right? But I couldn’t. And of course, they also offered me the possibility—if I wanted, to work with them as an informant—and this is another kind of pressure and a threat from them so I was not really secure. And then finally I had to leave and I went to Sydney, Australia to get more open space and be able to do what I want to do. Though actually I couldn’t do public performance there either—but for a different reason. So I spent a couple of years there, but you know, it was far away though I found myself more free. But then I was always thinking about Indonesia because Indonesia is for me, even today, the source of my inspiration and close connection. So then I went back to Indonesia but the situation didn’t change.

The second problem happened in 1993, so ten years after the first, I had this solo exhibition in Jakarta, and the piece called Etalase and the painting Lingga-Yoni, that is what caused me trouble at the time. I am probably the first Indonesian artist who received a death threat in my country. At first I tried to discuss it with this group of radical people. I also wanted to learn to understand what might cause that kind of anger because I have my own way, and I have my own ideas that I want to somehow express, which were different from their way of looking at it. And then we had a discussion, but somehow they didn’t really open themselves.

SUSAN:

Can you explain exactly what they objected to?

ARAHMAIANI:

What they objected to was, in that piece Lingga-Yoni, you see those Arabic letters, like ABC, and at the top it says: “Nature is a book.” This is an Arabic script modified for local language in Indonesia. So in this piece I say that nature is a book. So there is this Arabic script there in combination with this lingga and yoni and I am afraid they did not know the meaning of this lingga and yoni symbol, for them it was just a terrible image to show because it is an image of the vagina and the phallus. I tried to explain to them that for Hindus this is a sacred kind of symbol. It has nothing to do with something derogatory or dirty. But they didn’t accept this.

With the other piece, Etalase, it was the combination of items there, the Koran and a pack of condoms. For them it was a blasphemous thing.

SUSAN:

Just because they were in the same vitrine?

ARAHMAIANI:

That’s right. And I tried to explain to them that you have to see the context. I want to say through this display case something about the commodity, how everything has been commodified in today’s world and this creates a lot of problems. But then of course, those items can create some stimulation in your mind, when you think about the relation between them.

CHRYSANNE:

Were you fearful for you life?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes, of course. Because this never happened before. And everyone I consulted with, senior artists — they were all shocked, and everyone was just giving me advice to go away and escape and that I should not discuss this kind of thing with these people because their minds are really closed. So then I decided to escape and I ended up in Australia again but this time in Perth. I stayed there for one year.

CHRYSANNE:

Is it okay now when you return?

ARAHMAIANI:

Well, after 1993, I moved around to different places abroad. From Australia, I moved to Thailand, and many other places, and I lived at that time like a nomad, going from one place to another. That experience of starting with the military regime and then this kind of threat made me feel fear deep inside and I never felt comfortable and secure, so I always had to be on the move somehow, but that has been my life. So that’s what happened. But so far there are no other threats, or anything like that.

Two years ago, after I had worked with some of these Tibetan monks, I started doing research on Indonesia’s Buddhist past, which was really interesting. History books in Indonesia always consider this as a mysterious period, because they didn’t have much information and yet the largest Buddhist temple in the world is in Java. Anyway, that is an Indonesian problem. Then I got word from friends from many parts of the world who were doing research on the Buddhist historical aspects of Indonesia and I got to learn more about it. And then I started writing about it.

I used to have a column in the largest newspaper in central Java. For four years I worked as a columnist and I often brought up critical issues about the practice of Islamic culture and sometimes I would get some sort of comment or questions: “Why are you always criticizing Islam?” But I have my own opinion and I wanted to make some sort of contribution, because I come from a Muslim family as well, although in my mother’s family they are more like Hindu and Buddhist and Animist, they are not really Muslim in practice, so I have this mixed background in myself. I studied and made investigations into the Buddhist past about Lama Atisha or Jowo Atisha. Lama Atisha had a strong connection to Indonesia because he used to come and study under Lama Serlingpa or Darmakirti in Indonesia, I am talking about one thousand years ago, right? And that was my last essay before they fired me as a columnist from that newspaper.

SUSAN:

Were you fired because they thought you were too political?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes. Because then I got some calls from people and they said, “Are you a Muslim?” And I said that I am. “Why are you bringing up this Buddhist stuff?” And I said: “Why not. It is a part of our history and it is also the heritage that I received from my ancestors and this is important for us.” And I can go on and on about how important this history is for us, to learn about ourselves, to be able to go further.

CHRYSANNE:

So there is a threat from other ways of thinking?

SUSAN:

Was it Suharto who suppressed Buddhism or did that happen before his regime?

ARAHMAIANI:

From what I have learned so far, it happened long before, even before Islam came. Some people have this theory that it is because of Islam that they don’t want this Buddhist past to be considered important. Maybe it has a truth in it, you know, some Muslims aren’t really open and don’t respect other beliefs. But from what I learned, Buddhism was already suppressed a long time ago.

There was a book written in 1535 by a Javanese called Pararaton and it is a story of the book of kings—a historical book about the lineage of the kings of Java. You can read in that book about the wife of the king, whose name is Ken Dedes, also known as Pradnjaparamita, and of whom there is a statue that is supposed to be the most beautiful statue ever made in Indonesia. But in the story of Ken Arok and Ken Dedes, the woman is not really important, even though she was considered a special woman because any man who married her or born from her would become king. She is the origin of the lineage of kings. Yet, what is important is the king, not her. I started learning about Buddhism when I lived in Thailand in 1996, I got to know what Pradnjaparamita meant and what happened to this icon and how Buddhism was pushed aside. So it happens a long time ago.

If you read the history of Java and Indonesia from the twelfth century on, that was the time when Buddhism was declining, and from that time on until today life became full of violence, especially among the elites. Family members were killing each other and I tried to understand that—we don’t have enough historical research, but my intuition says when the belief in non-violence has been erased, then of course, people become so violent. Everything is possible and there is nothing to prevent it. And this is really sad. What happens now is like stepping backward to one thousand years ago. So I am really working on these kinds of issues. My ambition, if I may have an ambition, is to reintroduce the teaching of non-violence back home in Indonesia. This knowledge is not something new for Indonesia.

CHRYSANNE:

Will you incorporate this in your performance work?

ARAHMAIANI:

Well, I have done that already. But now I am really thinking about, with some of my friends in Indonesia who have a similar kind of conscience and who come from various backgrounds, Muslims and non-Muslims, building a kind of center, where there will be a meditation center, but also a center for inter-faith and inter-cultural activities, to relearn about past heritages and the usefulness of those heritages even today.

video ©2014 by MOMMY

CHRYSANNE:

Would you include environmental issues?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes. As I mentioned it will be inter-faith and inter-cultural activity and our focus will be on the environment. Because this is everybody’s problem. This will unite everyone with any faith background. I have been working on this idea the last two years and slowly getting support from within Indonesia itself.

SUSAN:

Now that we have mentioned the environment, in the room we are in (This interview was conducted at Tyler Rollins gallery in New York City during a retrospective exhibition by Arahmaiani in January of 2014.) there is a survey of your performance work and in one of the pieces, which is called Produk Gertoli, 2008, you have people posing the way they might in front of a tourist attraction but instead they are posed in front of an industrial accident. I wonder if you could tell us more about the context for this piece. Was the accident caused by Indonesian industry or by a multi-national corporation? What exactly happened at this site?

Produk Gertoli, 2008 (Performance, Sanata Dharma, Yogyakarta, Indonesia) photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

ARAHMAIANI:

That problem happened in East Java and is still ongoing because no one has been able to fix it so far. Although many scientists from many different countries and different fields try to solve the problem there has been no solution. What happened, I think it was four years ago, there was a company trying to drill for gas in the area but somehow they made a mistake and what came up was this poisonous hot mud instead of gas and since that time they cannot stop this mud from coming up. Twelve villages drowned already two years ago. So there are hundreds of thousands of people being displaced. And some people, even up to today are living in tents because this company is so irresponsible. And the owner of this company, Aburizal Bakri, was the Minister of Economy in Indonesia and even today he is one of the candidates for President in Indonesia, which is really absurd. And he, because at that time he was the Minister of Economy, he compensated some of these people, the victims, with money from the government. So it is so corrupt. And besides, he has been so irresponsible. There are NGOs trying to help the people. I and a group of young artist activists, are trying to do something through the work and by collecting donations to help.

SUSAN:

Was this piece shown in Indonesia? How was it received?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes. Everybody actually, almost everyone, knows about this problem and everyone is somehow disturbed because the government cannot handle it. It’s so frustrating, right? So when I had this work executed, people were like, “Yes, right.” After that we had this activity of a charity and people tried to do something about it.

SUSAN:

The government didn’t try to censor the show?

ARAHMAIANI:

No. Actually, they just don’t care. And this is what is really horrible in Indonesia. The system is becoming so corrupt. So many government officers and also Parliament members are involved in corruption. Big cases. More than three hundred Parliament members in Indonesia are already involved in corruption cases. It’s really too much. They don’t have this sense of responsibility at all. So even when there is this big catastrophe and people suffer, they don’t care.

CHRYSANNE:

You’ve been in many biennials. How do you feel about the exposure of your work within that context?

ARAHMAIANI:

In the biennials that I have experienced people usually try to understand the work itself, and the artist has to really try to explain what she is doing and what he or she tries to express and if there is a message, to clarify it. And there is always interest from different groups or writers, which is also usually serious, so it has been something stimulating for me. For example, when I was invited to the Lyon Biennale in France. In Australia or Japan or a third world country we have some kind of connection but the Lyon Biennale seems to me about the Western trying to embrace a few other cultures. I had a long discussion with the curator, who had worked before to invite artists from non-Western cultures, and in this Biennale he tried to further this kind of thing.

CHRYSANNE:

You had an exhibition in Amsterdam at the Museum Van Loon, the mansion of a family who were involved in colonial Indonesia. Can you talk about the photographs you inserted into the context of this rarefied Western mansion?

ARAHMAIANI:

This museum used to be the house of the Van Loon family and the Van Loon family was the founder of the Dutch East India company which colonized Indonesia for around three hundred years. So in the context of the past colonization of Indonesia, I focused on the issue of slavery. Because slavery is a problem not only of the past but is still going on today. From what I have learned so far most of the slaves are women. I have been working for the last four years dealing with this problem of Indonesian migrant workers. There are now seven million Indonesian migrant workers scattered in countries like the Middle East, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and a little bit here in the U.S. and Europe. And ninety percent are women.

SUSAN:

Are they domestic workers or sex workers?

ARAHMAIANI:

They do everything possible. Some of them are also trapped in human trafficking. A serious problem. So then I did some research with help from the curators of Tropen Museum. They helped me to find material from the 1700’s, when slavery was started in Indonesia by the Dutch colonial power. Last year, there was a celebration in Holland commemorating the elimination of slavery; one hundred and fifty years since the elimination of slavery. And I said, “No, that is not true. It is still ongoing.” And it was a good moment to bring these things up in Holland. So my idea, as you can see, was actually doing a quite simple performance. I recreated the style of the dress of the slaves from the 1700’s and in this performance I posed as a slave, standing or sitting down in this house, this mansion. So the background is very luxurious and my costume is very simple. When the photographs were done, I made the photographs look like a painting, with the help of the photographer. They were made in such a way—it looks like a painting and then I put it next to paintings of Van Loon. Or in places in the house where there are paintings of royalty. So this was a kind of intervention because I really want people to pay serious attention to this problem because it is an ongoing problem today.

SUSAN:

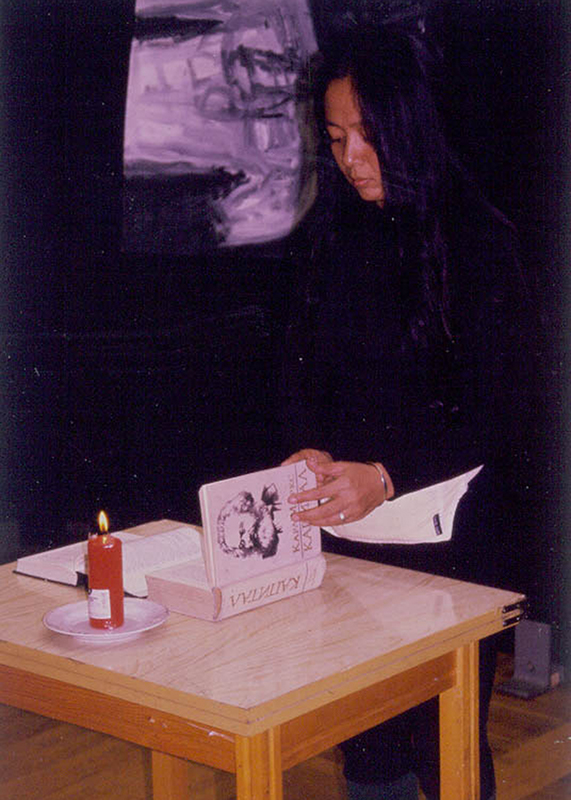

I want to ask you about the documentation in the exhibition of another performance called Burning Bodies, Burning Countries that took place in Kazakhstan in 1998. In the documentation of the performance it looks like you have a book by Karl Marx on the table and this is after the Soviet Union dissolved. I would like to know more about the content of the performance and how people there reacted to it.

Burning Bodies, Burning Countries, 1998 (Performance, Musée de Castieva, Almaty, Kazakhstan) photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

ARAHMAIANI:

Actually the two books are Das Kapital by Karl Marx and the Koran (Al-Quran). What I did, actually I chose a certain page that I thought somehow relevant still and then I tore it out and then I burned it. This action was my expression of my understanding of the text from the Koran and the text from Karl Marx.

SUSAN:

So the books were burned?

ARAHMAIANI:

No. The book was not burned, only the pages that I thought were relevant to the situation today.

SUSAN:

But from each book?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes. By the action of burning I wanted to make this thing alive, because if it is only there as a text, it is just dead. But by burning it, it is like turning it into a spirit.

CHRYSANNE:

Do you see burning as an act of purification?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes, something like that.

CHRYSANNE:

That would be something very much within Buddhist thought and practices.

SUSAN:

And how did the audience respond?

ARAHMAIANI:

Well, it was actually in Kazakhstan, so of course they were Muslim. I was invited by a group of artists and young activists so it didn’t create any problems because they understood and agreed in a way, that something in the Koran and something in Karl Marx is still very relevant to today’s situation. And actually, we need to think further about it.

SUSAN:

With Marx, it was a bit of a “baby with the bathwater” situation. Once the Soviet Union was disbanded, Marx was completely discredited along with “communism” but they weren’t the same thing.

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes. One is the political system and one is the thinker.

Talking of this Buddhist thinking, for example, what I find fascinating is that I did a lot of things that I didn’t really realize were done in a Buddhist way. Only later I understood, when I started to learn Buddhism and got to know more after meeting Tibetan Buddhist monks. I could look back and think, “I did it,” and I thought this was my own artistic and unique way.

CHRYSANNE:

Recently you posted a video discussing the water issues in Tibet. Did you have any feedback or any reaction from the Chinese government regarding that video?

ARAHMAIANI:

Regarding the video itself—there are some friends, not Chinese friends, who gave this a positive response. But actually I have been addressing this issue since I started working in Tibet, which was in 2010. Through my essay, through a conference, everything. The Tibet plateau is the water tower of Asia and this is the reason why I go up there. At least seven of the largest Asian rivers’ head waters are actually in the Tibet Plateau: the Yangtze, Yellow River, Mekong, Salween, Brahmaputra, Indus and Ganges. And because of that, more than two billion Asians are living from that water. The situation now is alarming, because the glacier and even the permafrost up there are melting rapidly and that also causes floods. In India last year more than five thousand people died in these floods and in Thailand two years ago more than 10 million people had to be evacuated. Also in the southern part of China, this is a regular catastrophe every year, every rainy season, and there are also mud slides. It happens in Southeast Asia, China, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The flood in Bangladesh was really terrible three or four years ago. And Pakistan, I think is also part of this area that has its water coming through these rivers.

So this is really a very important issue that Asia has to address and I mean not only address it, but also find a solution. We cannot just expect other people to do it. So that is why I just decided that I will go up to the plateau and work with the monks and the lamas. And fortunately they were so open minded, although at the beginning we didn’t know if it would be possible or not because everything up there has to be approved by Chinese government. And Tibetans are not so free to do what they want to do, as you know. At the beginning we thought, just find a good idea and try to do it. So I was thinking about a practical approach to start dealing with this problem. And besides, there is this other challenge, in the monasteries in Tibet, they don’t have a science education background. Although there are some cases of people educated in India and coming from India, they have to do a lot of things, teaching Buddhism, so they are not expert on the environment. So this made me think, “Yes, let’s do something practical.” So we started with garbage management, which was also a little bit difficult, because the monks were like, “We do it?” And we said, “Yes, we do it.” And they said: “Oh really, why don’t we pay people to do it?” And I said, “No, we don’t have money for one thing and second, this is the way to raise awareness about environmental problems and also raise individual responsibility.” It is so remote and such a high altitude, how can we develop a system of managing garbage, like they do in a big city for example? It’s so difficult there and we had to find our own way.

CHRYSANNE:

You planted trees?

ARAHMAIANI:

Yes.

CHRYSANNE:

Do you think that has any relationship to Joseph Beuys’s trees? We are surrounded by his trees and stones here in Chelsea.

ARAHMAIANI:

The planting of the trees was our second step. Managing the garbage came first and the local authority seemed to be happy so then what was the next step? And I thought, there was this lama, the thirteenth Lab Rinpoche of this monastery. Actually, he started planting trees one hundred years ago and he made a prediction, that this is what is going to happen, that this is what we will need to do in the future. And I said this is not my idea this is your lama’s idea and wouldn’t you like to plant more trees. And they said yes. So we have planted almost one hundred thousand poplar and pine trees.

I learned about the work of Joseph Beuys, actually that is my specialty because two of my teachers, one from Germany, Uwe Pott, who is also an artist, and the other from Holland, Ad Geritsen, they somehow suggested to me to focus on the works of Joseph Beuys. And I asked them why they want me to study this Joseph Beuys and they said there is a relationship between your work and his work. Fine. So it’s something I have to find out. Anyway, I studied there only for one year, although I was supposed to study for three years, but Mr. Suharto, the dictator, created another problem, because he was unhappy that Minister Pronk from Holland criticized him on the issue of human rights abuse in East Timor. Mr. Suharto was so angry that he kicked all the Dutch out of Indonesia. But then of course, we Indonesians who received grants from the Dutch, we had to go back to Indonesia.

I really get inspired by Joseph Beuys’s work. Somehow I can see a clear connection and understand his work and clearly, appreciate it so much. But of course, I also realize, I have to put it within my own context. Although, of course, Joseph Beuys was also doing cross-cultural things with his story of being stranded in this area where he met the Mongolians and had some experience with their culture. That connection is so clear to me because that was already my focus: cross-cultural issues, especially between non-Western or Eastern and the West. Sometimes there is a conflicting situation, although later on I also found out that there were similarities, because at the end of the day, everything is connected through universal values, which are accepted by everyone, no matter what their cultural background is.

Do not prevent the fertility of mind, 1997-2014 photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

SUSAN:

The melting of the permafrost, for example, is not something that can be solved locally. That is an international or global problem.

CHRYSANNE:

And the Chinese are building many dams, which makes it even worse. There is even the worry that the Chinese could cut off the water to India and this is a political and financial issue.

ARAHMAIANI:

So actually, the melting is not caused by the Tibetans. They are just the victims. It’s global warming, that’s the cause of it. It has to do with our modern life style. It’s a huge and complex problem but this is also one reason why I go from one country to another, because I want to have this network, build a network, among those who are concerned about this problem, wherever they come from. But especially try to go through this community network, not only in Asia but wherever, because this is our global problem. And also to really do something about it. I mean, I am aware that I am mostly working on the grassroots level and we can’t do this ourselves because it also depends on the decision makers up there. But now people are really trying to change the policy. And of course it is not always easy because there are the interests of different groups. Anyway, what I try to do is build this network of activists. This is also what I did in India. I went to Madras University and I gave a lecture there and I started to have this discussion with the students, both Indian students and Tibetan students in exile and to think about alternative solutions, whatever we can do. And this is related to the idea of community based art projects, which I have been working on for almost twenty years, working with various communities in Indonesia but also in other countries. So this is not actually a new thing for me. But now with this focus on water, we really have to learn more because I am not actually an environmentalist, I am not educated as an environmentalist, but somehow the situation calls me.

We are trying to have a connection to environmental organizations. I have been in contact with the director of Flora Fauna International in England and many organizations in Germany. Germany is one of the pioneering countries in terms dealing with environmental problems. And I started last year teaching at the University of Passau in the southern part of Germany. It’s the department of Southeast Asia Faculty of Philosophy. And this is interesting for me and also interesting for them, to have a visiting professor who is not a philosopher and academic but an artist. According to the professor, they explained to me that they are having problems, in the context of Asia and Southeast Asia in particular, they are always left behind because it is so far away. Asia and Southeast Asia are very dynamic places now, where change happens so rapidly. So they always have to keep up with the real thing, they can’t rely just on the theory.

SUSAN:

The one place we haven’t mentioned is the United States. And in this exhibition alone there are two Coca-Cola bottles. Obviously, Coca-Cola is a symbol of consumerism but it is also a symbol of American imperialism. Because everywhere that America went, Coca-Cola went. And America is probably the most egregious polluter and set the example for China and India and has a very difficult time now telling them to stop doing what the U.S. did for so long to become a rich country. So I wonder where America fits in for you, because it is being alluded to in these works.

ARAHMAIANI:

You do see the American flag in that piece there. And this is a very important point. I am addressing the problem of globalization and that is somehow connected to imperialism. In this case it is America. In the context of Indonesia as a country it is very important because after the colonization by the Dutch, Indonesia was considered to be independent in 1945, and actually the first Indonesian president Sukarno, was really trying to make the country independent and he formed this alliance with a group of countries and other leaders from these once colonized countries. But he failed in his attempt to make Indonesia and these allied countries really independent and this had to do with American control and power.

What I can see is that the independence of Indonesia from Holland was true but then it was an act of handing down Indonesia to America, basically. Because Sukarno was replaced by Mr. Suharto, in a coup-d’etat and Mr. Suharto was supported by America and its allies. After Mr. Suharto was in power he opened the country widely for foreign investment and it changed the country, it changed the lives of the people. For example, Indonesians are mostly farmers, maybe eighty percent, and since that time, with the dependency on and support from America, the Indonesian government introduced the so called Green Revolution program where all these farmers had to change their way of farming and get seed from America and also fertilizers and everything, including tractors. And since that time, the way of farming is not organic anymore and depends on resources coming from America. The price is somehow decided by those companies and also it is not good for the environment, it is actually destroying the environment. And this is just one example. There are many things. Like deforestation, mining. And everything is, how should I call it—looting of the country by these multi-national corporations. And people suffer in these countries because the source of their food is gone now. So this creates social disintegration and destruction of cultures. We have all these problems now. I mean, I am not against improvement of life but if modernization means just the looting and destruction of the earth, I don’t think that I can go with that.

CHRYSANNE:

You did some of your installations about this.

ARAHMAIANI:

I try to bring this problem up in my pieces, in my installations and in my performances and also in my painting, and in my writings. There are many different ways and strategies and it also depends where I am going to show the piece, because what is the most important in my work is that I can communicate the idea, because I have something to say. With this Coca-Cola bottle for example, I think it is also something that people understand, it is not hard to explain, although of course everybody can have their own particular interpretation of it. Right?

SUSAN:

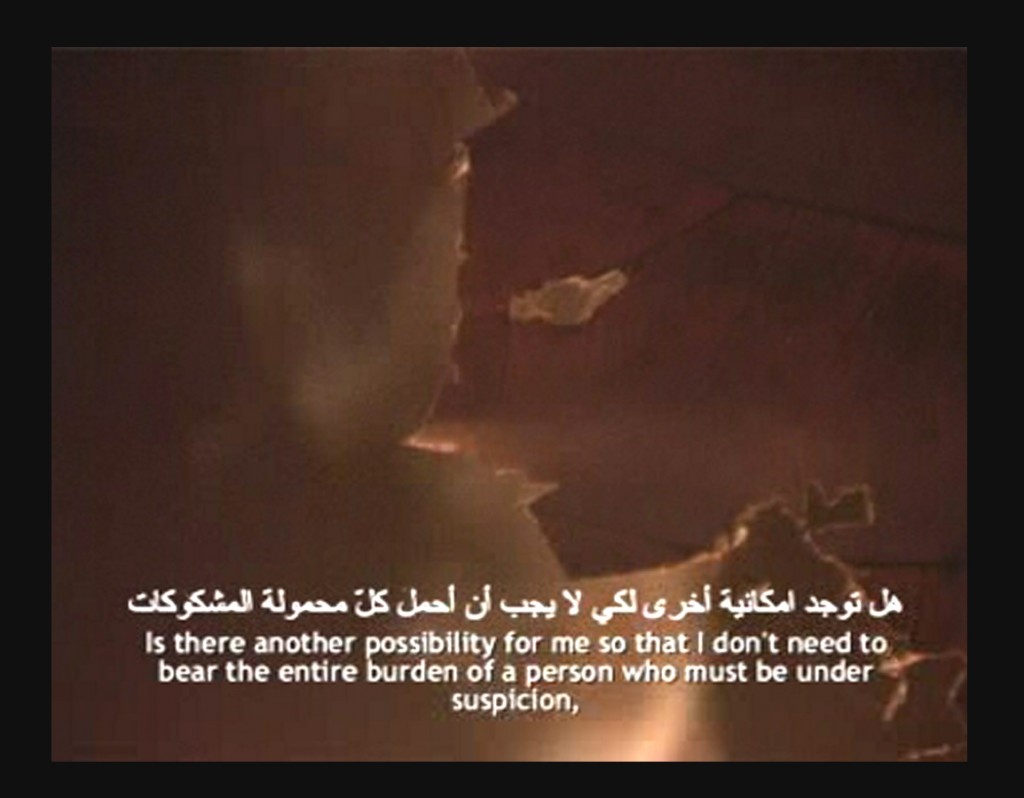

I wanted to talk for just a moment about the video that is on view at the gallery. The images on the screen look almost like shadow puppets but you realize that the puppets are actually leaves that have been sculpted to create these shadow puppets. I thought maybe you could tell us the story of this video work.

I don’t want to be part of your legend, 2004 (single channel video) photo courtesy of the artist and Tyler Rollins Gallery

ARAHMAIANI:

I am referring to the story of Ramayana. In the story, Sita, the wife of Rama, was kidnapped by Ravana, the king of evil. She was released, but when she was reunited with Rama again, he was suspicious that maybe something had gone on with her and Ravana. So it was a mix of jealously and distrust, I guess. But in this piece, I am focusing on Sita’s question, because Rama asked Sita to go through tests. She had to go through fire, and if she was pure she would be okay, but if she was naughty, she would be punished. In this video, this is Sita’s question, “Why I am the one who has to be tested? Why not both of us?” So that’s on one level. And by using shadow puppets, it somehow relates to the culture where I come from where we have a long tradition with the shadow puppet. And with the use of the dry leaves, I want to connect to the environment. Also, it has another level of symbolism, because falling leaves can somehow generate new life. So it has many levels of meaning. I hope that somehow people can read that. But everyone has their own perspective so I let them have the freedom to interpret any way.