Judith Braun photographed in front of her studio door on the

Lower East Side, November 2013 © 2013 by Susan Silas

SUSAN:

Looking at your very early work I could not help but notice that you were a gifted realist painter, and when artists have that skill they are loath to give it up, and that one ability can take precedence over their ideas, because it is gratifying in and of itself, and because not everyone can paint that way. So I am wondering how you let that go? This is not to say that what you are doing now does not involve specific and refined skills, but they are not the same skills.

JUDITH:

That’s a good question. That was a really big turning point. It’s a very natural place to start for a lot of artists. It’s something that has a goal to it. You know when you are getting good at it, you can look at a master and you can feel when you are getting better, and I did love doing that. But when I was in graduate school I had professor, Mark Greenwold. I don’t know if you know him. He just had an amazing show at Sperone Westwater—the figurative painter. He was very smart, very articulate and he was a strong influence over me. He encouraged me to paint well, but he also encouraged me to be myself and take myself seriously, and so what I really found after graduate school is that I had more parts to myself. I wanted things to move faster and the paintings I made took a very long time. It’s funny, but recently I was looking through something I did at that transition period called “Fuck Mark.” It was about me going through that transition between aspiring to paint like Rembrandt and realizing I had other ideas to pursue. I started to take photographs of my meticulous paintings, reducing them to xeroxes, and then writing on them. On one of them I scribbled “Fuck Mark!” So that is when I started to make the paintings really small and writing words on the paintings as well. I made a really small painting of a cat and wrote My Pussy on it. That was in 1988, for my show in the East Village called White Girl Paintings, so I was beginning to express this side of myself, a kind of playful irreverence.

SUSAN:

And was the reaction to this new work pressure to continue painting as you had before; people asking you why you weren’t making those paintings you were so good at making?

JUDITH:

Yes. I felt really strong, and it gave me a kind of confidence to do the realistic figurative painting that was so historically valued, and people do tend to respect it still. And I did some good paintings—I was really into the painting of transparent skin. But I think that was an important rebellion on my part; to give that up and find who I was otherwise was a risk, but a great feeling of liberation too. And Mark Greenwold, we’re still friends, was very supportive all the way through. I think if I cared at all along the way what anyone thought, it was about what Mark thought. It’s hard just to believe in yourself and be sure that you really have something to offer. I think people you respect have to give you that affirmation to build on.

CHRYSANNE:

I’ve noticed your creative journey explores the body from the figurative paintings to the Xeroxes to the most recent wall installations.

JUDITH:

It’s true. There is obviously a connection.

CHRYSANNE:

What are your thoughts looking back at your 30-year transition from painting the body to using the body as the vehicle?

JUDITH:

I hope this doesn’t sound argumentative about that point. Since I started doing the finger print work—people have started to think I am a body artist and they talk about the performative aspect of the work, and I try to reel it in a little because I don’t want them to be performances. As soon as people began asking to videotape me actively drawing, and I did it a little, even in front of a public audience, then I had to back off. It was fun in a way, but it limited my own experience of making the work. I’m really a studio artist. I prefer to show the results, and let the process be a mystery.

I mean it is inescapable that we are human beings and we are using our bodies. I think about the wall drawings in this way: I am using charcoal, a carbon material which is the basic material of the earth and it’s also the basic material of the body and I am drawing with my fingers, and so they are all connected. And the symmetries I do are all clearly related to nature and the body and brain too, but I see it that way more on a physics level. I guess this is all to say that I don’t connect myself to, say, Anna Mendieta, as specifically a body artist.

CHRYSANNE:

But I wasn’t talking about it in terms of performance, I was talking about it as a physical act. Is there a reason that you wanted to do it with your hands, your physical body, rather than paint brush. I see something special about the body that reveals itself within your wall drawings. I am interested in the transition of painting the body and getting to know it and the breath of history within your work, not you as a performance artist per se, and wondering what made you use your body as a vehicle.

JUDITH:

Well, yes, I did like the raw simplicity and reductiveness of the approach. There was a very specific incident that brought about the first fingering wall drawing, at Artists Space, so you possibly remember it.

CHRYSANNE:

Yes, I do.

JUDITH:

That happened because I was doing these small pencil drawings (points to drawings installed on the studio wall).

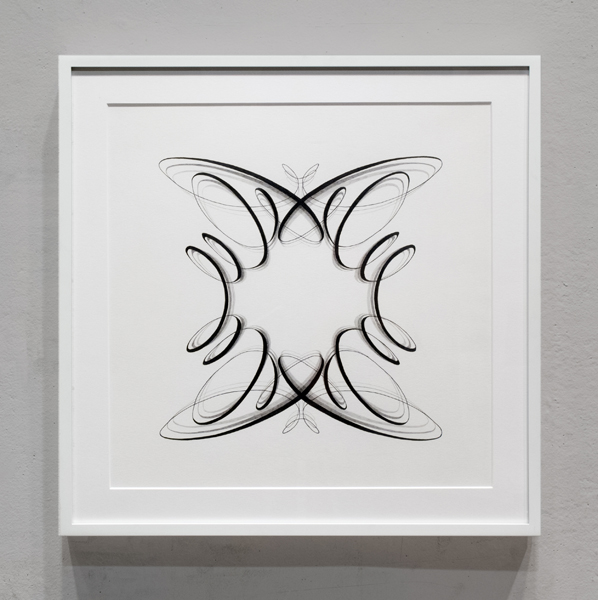

Installation of “Symmetrical Procedure” drawings, graphite on paper, “May I Draw,”

Joe Sheftel Gallery, NYC, 2013.

Now sometimes people think the large wall drawings came first but actually these came first. I had chosen these three specific parameters for my work, which were symmetry, abstraction, and using carbon materials. I had come up with these rules, so to speak, in 2003, and then in 2008 had a solo show at Fruit and Flower Deli, a small gallery on the Lower East Side. Raimundas Malasuaskas, who was visiting curator at Artists Space, came and loved the show and he wanted me to do something at Artists Space on a gigantic wall. So I was trying to think how I could use my basics of symmetry and abstraction and make them larger. I tried extending my arms with sticks with charcoal attached to the ends, and I was trying to draw symmetrically like that with both hands. You can picture it—sticks were falling apart and nothing was really working. But I realized that my hands, our hands, just naturally move simultaneously, the same way. It’s harder to do different things with your hands at the same time, the way musicians do. So I thought: “Wow I can do this, but maybe it would work better with just my dirty hands,” and I made a fingerprint on the wall. Wow, I noticed that the fingerprints were really interesting marks, very three-dimensional looking. They weren’t just flat smudges. And there was so much control and variation possible, just with pressure and gesture, like any other drawing tool. So I told Raimundas I’m just going to draw on the wall with both hands simultaneously, and see what happens. And I stuck to that very strictly for that first drawing, making sure the whole thing happened with both hands simultaneously. I moved the scaffolding down the 30-foot wall, repeating the same gestures and pattern from one end to the other.

“Fingering #1”, Charcoal fingering on wall, 12’ x 30’, 2009 at Artists Space, NYC.

The first Fingering.

I guess people liked it because since then I’ve been invited to do 18 walls. Each one is unique and site specific, but they all still fit within my parameters of abstraction, symmetry and carbon materials. I do love having a very large space to grapple with, on ladders or scissor lifts, but honestly I really like being in my studio, at a table, with a light, and a clean sheet of paper and pencil, where everything is very contained. It’s a different focus. I feel everything goes down into the point of the pencil, you know, rather than spread out on an entire wall, where it’s more like conducting an orchestra.

CHRYSANNE:

What took you to symmetry from doing the xeroxes? There was a break in time, in your art practice, correct?

JUDITH:

Yes.

video ©2014 by MOMMY

CHRYSANNE:

I read that your annual tarot reading inspired you to return to making art full time.

JUDITH:

Yes.

CHRYSANNE:

And you ended up with symmetry?

JUDITH:

Well, the tarot reading was not the door directly to the symmetry. Although it’s interesting that the card that led me to coming back to making art again is a very symmetrical card. I have it posted on my wall over here.

CHRYSANNE:

Which one is it?

JUDITH:

It’s “The Lovers”.

CHRYSANNE:

Oh “The Lovers,” yes I know that.

JUDITH:

I’m into tarot cards, but not as fortune telling. I just find that they act as triggers to learn things about myself. You know, it’s like I wanted to learn new things about myself, have insights, and it’s hard to get that. So, instead of going to a therapist, I went to a Tarot school for a while to look into it as a way of looking into my subconscious.

CHRYSANNE:

Where did you go to school for it?

JUDITH:

The New York Tarot School. It’s run by an older Jewish couple. I wanted to see how they do it and I learned that reading cards is very much a visual and psychological thing. It’s not like, well this card always means this, and this card always means that. It’s a combination of the card, the question, the placement and context, and things like that. I got really into it for a while but then I decided it would be good to just do it as an annual ritual—my own life evaluation. So in 2003, the big question for me was how I felt about not making art anymore. I’d had my first time around as an emerging artist in the late ‘80’s early ‘90’s, and then got sidelined. Divorce, finances, parents’ illnesses, daughter in college, loans to pay, and so I couldn’t do my work for a while. I thought it would be a temporary thing, but that actually extended into nine years. Even though I’d found other things I liked to do; tango and swing dancing were my hobbies, and doing faux finish work was paying my bills—something was missing. I wondered if I’d look back and say: “So you were a tango dancing faux finisher?” Would that be enough? The answer was no.

So when I got “The Lovers” in the reading I didn’t think it was about meeting a new boyfriend; I realized that it was about a relationship inside myself that was not 50/50. There was a dominant voice in there and there was another voice that wasn’t being heard. So I asked myself what was not being heard, and this little voice inside said, “It’s me, the artist.” But the dominant voice was always discouraging that voice, saying “Who do you think you are?! You can’t just jump in and start again. You are 55 years old.” That voice had a million reasons why I couldn’t do it.

But I asked the tarot cards seriously and I had to take them seriously. Why do them if I’m not going to pay attention to what I think they are showing me? So I made a decision to try again as an artist. I would reorganize my life to make time and space, and try to have “one more show.” I didn’t want to have too high a goal! That was when I decided to rent the back of my apartment to tenants and just live in my studio, so that income would cover me. And I quit the faux finish business and I started to make a new body of work.

Oh, and this is important. I decided to dedicate myself for three years to see what I could do, if I could get something, anything, started. I thought that was a reasonable time frame. I started to explore new work in many directions behind closed doors. I was looking for something I would love doing, actually be dying to get to work on every morning, something that would be an ongoing, inexhaustible project. And gradually I found that what I really, really liked doing was sitting at a drawing table with paper—blank paper and pencils. And so that’s when I started doing the small drawings I called Symmetrical Procedures. Actually you see that drawing over there? That’s where I started. I started making a line, a curved line, and copying it, in reverse. The concentration of copying in reverse is really, in itself, very engaging and meditative. After I’d made quite a few, and liked the process and results, I narrowed down what they were about. It was abstraction, the symmetry and the limitation of black and white. The abstraction kept them free to be anything, the symmetry made anything into something. It was freedom and discipline, and that suited me. So I started using those parameters, which is what all of this work is still about for the last 10 years, and I’m not at all tired of doing them yet.

But going back to the 3 years, within that time I was in some shows. The most important, to me, was with the Pierogi traveling flat-files. So this allowed me to add time onto the three years because something had actually begun to happen!

SUSAN:

So tell us a little bit about how your career evolved after Pierogi, because it is interesting to hear from women who, for various reasons, emerge a bit, get sidelined and then re-emerge. How did that end up happening for you?

JUDITH:

Okay. It’s different for everyone, but for me I think it was having my goal and establishing the timeline. I think doing the three-year plan was really important because then I didn’t question myself every day when I came into the studio. Once I had decided I was going to do it, there were no questions. And then I set up something else in my mind, which was to work “as if” I had a solo show coming up. These were very strong mental mindsets. I started to use everything I’d learned how to do in my first go-round—like send work to juried shows in some town somewhere. And just getting in, and even getting awards, energized me. I also knew about non-profit spaces because I had done them earlier. White Columns, Art in General, and that kind of stuff. Every time I got into something I’d feel a bit more confident because my work was out there somewhere. And that would push me to reach out further, because I could say: “Hi, I’m in a show at such and such.” We all hate asking people to look at our work, hoping they’ll put us in things, it feels so desperate. But spring of 2008, while I was in a show at Nurture Art, I forced myself to walk around the Lower East Side, which was starting to have little galleries here and there, and I’d go in and have conversations with people.

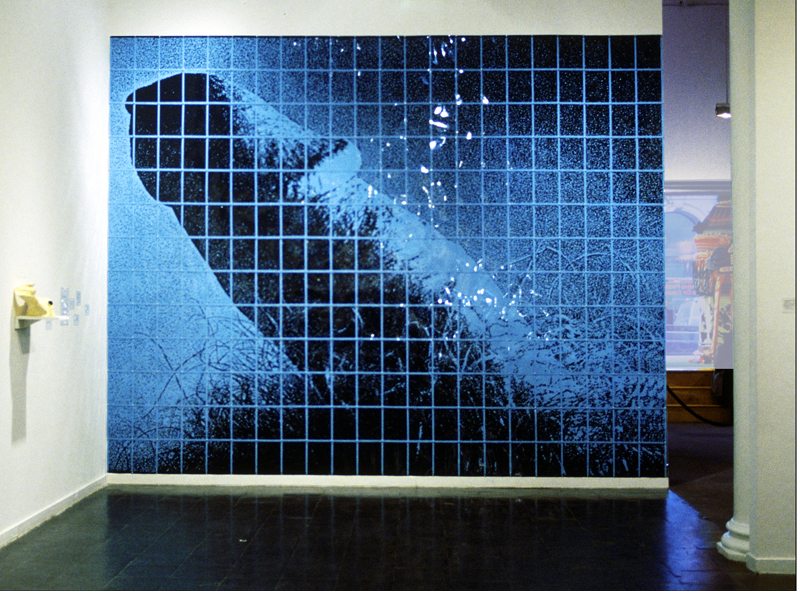

10) “Fingering #16”, Charcoal fingering on wall, 12’x 12’, 2013, at Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, Summit, NJ.

Finally, a really key thing happened. I walked into Fruit and Flower Deli, a small gallery on Stanton Street with a sign on the door that said, “Never open but always welcome.” The place was falling apart, with holes in the walls, but there was an interesting show up by Rainer Ganahl. Rainer’s an important artist out there but I’d been out of the loop for a while and didn’t know of him, so I was a little nervous. Anyway, the guy in the gallery, Rodrigo Mallea Lira, who called himself the “keeper” of the Fruit and Flower Deli, was explaining to me about Rainer’s work and I was trying to pay attention. Then he asked if I was an artist and I very daringly stated that I made these great drawings, told him about the show at Nurture Art and pulled out this little CD that I was carrying around, with a tiny picture of one of my drawings on the front. In a split second he exclaimed excitedly: “This is what you do?! Do you have more of them? Where’s your studio?” When I told him it was around the corner, he literally closed up shop and we walked over here. Just like the sign on the door said, “Never open, always welcome.” So he took two framed drawings off the wall, went to Art Brussels the next day, and sold them both.

Okay? So based solely on the art, not on connections or mutual friends, it just happened. It’s a really important story for me, but it’s not a story that can be replicated, as if it can just happen if you do this or that. There are so many invisible parts to how and why it happened, for both Rodrigo and me. We’ve talked about it many times. He saw something in my work that was nothing like Rainer or his other artists—he had Nicolas Guagnini, Julieta Aranda, David Adamo. These are all established artists that are more conceptual than me, on the surface. So much can be traced back to this encounter, and the solo show we did that summer, and I both give credit and take credit for making it all happen.

“Blue Penis”, Xerox on paper, push pins, blue vinyl report covers, 12’x14’, 1994, Bad Girls show at New Museum of Contemporary Art, NYC.

Sometimes when I look back at the important people for me: I think of Mark Greenwold, and Rodrigo, and Raimundas, and my ex-husband who built me a studio and gave me free reign to go running to New York my first time around. There was Stefan Stux in the early days, Colin de Land, Bill Arning. Quite a few men. But there were a number of women too who were very pivotal and equally important to me along the way. Souyun Yi gave me a solo show at her gallery in 1990 and put 100% confidence in me, Ann Philbin gave me a large wall in her debut show as director of the Drawing Center, (she’s now director of the Hammer Museum), and Holly Block had me side by side with Glen Ligon at Art in General (she’s now director of the Bronx Museum). And then Marcia Tucker put me in the Bad Girls show at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in 1994. And I have to mention Roberta Smith, who gave me such a generously positive review in The New York Times last year. I mean, that was an amazing gift from such a preeminent art critic. It was a huge boost to my spirit. Which, if you don’t mind my inserting here, came in the midst of my chemotherapy treatments, following a double mastectomy for breast cancer. Okay? So you can imagine I appreciated the boost!

CHRYSANNE:

How did you meet Marcia Tucker?

JUDITH:

I think Marcia saw my work in a White Columns benefit where I had a piece titled Read My Pussy. She was there with collector Penny McCall, who has since passed away, and who bought my piece. It was around that time I was contacted by Marcia to do a studio visit for the Bad Girls show. And here I’m going to share another very meaningful story to me, that’s kind of private, but important. The night of the opening of Bad Girls, Marcia and Alice Yang, her co-curator, came over and told me that I had been the inspiration for the show.

“Read My Pussy”, Xerox on paper, push pins, vinyl report covers, 12” x 144”, 1990.

Solo show at Souyun Yi Gallery, NYC

SUSAN:

That’s a very wonderful thing to be told.

JUDITH:

It sure was! Her telling me that gave me something that I can have inside even today.

CHRYSANNE:

When you dropped out did you feel an emptiness? Was it a long decision coming?

JUDITH:

It was complicated, and yet simple. I thought it was going to be shorter time span, just to get my finances going, maybe a year or so. And I was also excited about being single and on my own, so there was adventure about it too. I wasn’t missing making art right away. But I started to realize that the art world was not waiting for me either. The train left the station without me, and I was like: “Wait a minute. I’m not going away forever.” But they were gone. And then during that time I found I didn’t want to hang around artists at all because I didn’t want to hear about their studio visits and what shows they were in. So I was torn, it was a withdrawal from both sides and a mix of feelings, up and down.

That grew more clearly painful as time went on. I began to feel like the skin I was in was not really mine. I didn’t feel at one with my outer and inner self. I can now say that when I started making art again it was as if put on a skin that fit perfectly. I knew who I was again. So, long story short, that’s why I like doing my Annual Tarot Cards!

CHRYSANNE:

What’s interesting about that card is if you look at “The Lovers” card the hands are held up in the air symmetrically which you have done numerous times here.

JUDITH:

Hey, it’s so true, I had not seen the symmetry in the raised hands on the cards as specifically reflecting my own drawing process as clearly as that before!

CHRYSANNE:

And what do the Portals mean to you? How do you view the Portals? Is that a passageway to another way of being?

JUDITH:

In the groups that I’ve done that are called Portals?

CHRYSANNE:

Yes.

JUDITH:

They began basically as the reversal of the other drawings, just within my seeking variations and creating groups and subgroups, all overlapping and growing out of one another. I just called them Portals because they had the dark spaces in the middle. It didn’t have a lot more meaning than that. I always just do things and then see meaning afterwards. I choose names for the groups that are simple and descriptive, and just a bit suggestive. Some of the other groups are Lanternals, Orbitals, Rimmings, Emblems, Amulets, things like that. Otherwise the individual pieces are titled by a code of numbers and letters, but once I had dozens and dozens of drawings, I needed the group names so I could refer to them more easily. It was getting complicated!

SUSAN:

Do you think that feeling progressively more entitled as a woman artist allows you or women in general to let go of specific feminist content in their work? Or do you see your trajectory as having nothing to do with that? Because, it seems to me, your early work was overtly feminist in content.

“Sacred Order of the Burning Bush”, Xerox on paper, push pins, 30’ x 30’, 1993.

Kunztlerhaus Bethanian, Berlin, Germany

JUDITH:

I had that period when I did Read My Pussy, and it was a lot about my ownership of my identity as a woman. I think that’s a big part of feminism. I had also changed my married name, from Weinman to Weinperson, as part of a feminist artist persona. But when I started my new work, in 2003, I dropped the sexual and feminist content mainly because I had changed a lot as a person. We grow and change! I’d done realistic narrative paintings and I’d done the xerox work that was graphic and sexual in subject matter and attitude. I think I was just in that stage where I was interested in how to be reductive, how I could contain all of myself, and my history, in a sort of poetic way. So I wasn’t doing it out of female confidence, but maybe just myself as a more mature person. I think it’s more about courage than confidence.

SUSAN:

I also wanted to ask you how having a child played into your career trajectory because obviously, or maybe not so obviously, but I think it’s obvious—women tend, no matter what anybody says to the contrary, to do the bulk of childcare no matter how equitable their relationship supposedly is. It’s much easier for male artists to have children than it is for women artists.

JUDITH:

Well, I think having a child was a very grounding experience. I don’t know who I would be today if I hadn’t had a child and been forced to make some very realistic decisions about life. It’s just a unique maturing experience. I had been married and I had to escape the father of my daughter because he was abusive. I was a single mother for a few years. During that time I decided to go back to school and I chose a “school without walls,” making up my own degree program at Empire State College. It was Art and Design, because something slightly career oriented seems wise. Being a mother forced me to start making better choices, including marrying a nice man the next time, someone who was kind and supportive, and who adopted my young daughter. And he paid for me to go for an MFA. I am forever grateful! Being a single mother and an artist would have much harder, near impossible, without him. But returning to the question of motherhood, having a child made me learn how to organize my time. Getting up early, going to sleep early, I’m still like that. I knew what day I was in the studio, how many hours I had, what day my daughter was in day care, what day my mother was helping. So that was all good for me. I also feel that being a mom is the one way that I am selfless; knowing that there is actually a person I’d throw myself in front of a bus for is a good thing for me to know.

SUSAN:

And how old were you when you had a child?

JUDITH:

I had her when I was about 28. Now I’m 66 and she’s 37.

SUSAN:

Just out of curiosity what is she doing?

JUDITH:

She’s just starting a Master of Social Work program at NYU. She’s done a lot of other things, writing, graphic design, teaching, personal chef. She’s following her path!

CHRYSANNE:

Is there anything advice you have for younger artists? Or even a middle-aged artist, or an old artist?

JUDITH:

There are so many things to tell people for advise, but I guess the basic idea is set your goals and keep working. Your goals, no one else’s. And I happen to think practical things like time management are very important. Practicing making decisions and following through. A lot of people are very random about how they go about achieving what they say they want. I think it’s good to say it out loud, name it, write it down too, and then find reasonable steps to get there. I am a big advocate of finding Step One.

Thanks for finally writing about > A conversation with Judith Braun | MOMMY < Liked it!

I am so happy to have read every word in this article. Thank you. So much wisdom shared.